Yesterday morning my graduating first-grader put on his private school uniform for the last time this year, and though he doesn't know it yet, the last time for the foreseeable future.

Last week we got the official letter from the school's financial aid office, and while the news was what we expected, it wasn't the full scholarship we needed. Even with the 50 per cent reduction we've been getting, we've never really been able to afford the monthly tuition. And although Patrick's new freelance gig is already bringing in more than what he earned at his corporate job, cash flow is still nail-bitingly erratic. Over the past eight months, a private school education has migrated from the "do not touch" column, to the "luxuries we can no longer justify" side of the ledger.

Mostly, I am okay with it. Placement in our neighborhood public school is highly coveted. I have been approached twice by people outside the district wanting to "borrow" our address to get their kids in. We already know lots of the families whose children go there, and I want my boys to grow up feeling connected to their immediate community, not always being chauffeured out of it.

I tell myself to think of it as a trade-off, not a loss. Now that we are off the corporate grid, my dream of spending summers in Newfoundland is not as far-fetched as it once seemed. Time is our own, and one year’s tuition would easily cover airfare for all five of us. In terms of an education for the children, that beats private school hands down, in my opinion.

Still, I am a little sad. My son's two years of private schooling have been idyllic. He has been so happy and nutured there, and I don't have the heart yet to tell him that he is not going back. What the school lacks in diversity and excitement, it makes up for in warmth and security. Back when we were first wringing our hands over schooling options, I wondered if the environment was too sheltered, too controlled, too unreal. But on days when I could gaze out my office window and watch my son skipping safely across the immaculate school playground, surrounded on all sides by an elegant wrought-iron fence, I would think maybe shelter is a good thing when one is very young and the world is very large.

But then, not everything I worried could hurt him was on the outside of the fence.

Few other middle-class kids attend his school. There are some, who are there because of their religious affiliation, or whose parents are two-income earners who simply rolled over daycare fees into private school tuition, or whose grandparents are footing the bill. But by and large, the students come from the city's wealthy elite. A memorandum in the school handbook obliquely reminds parents to refrain from sending limousines for the children on their birthdays. My son’s classmates spend spring break at luxury resorts and theme parks; summers at beach or lake houses. They have soda machines in their bedrooms and pools in their backyards. Yesterday he attended an end-of-school swim party held for his entire grade at the country club.

My son seems to have been oblivious to all of this so far. He looked just as much at ease in the club pool as he does in the community one we swim in. Since he started kindergarten, I have watched vigilantly for the first signs of self-consciousness, of any perception of lack, poised to put material wealth in perspective for him.

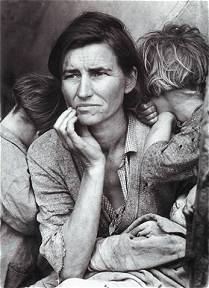

I am supremely unqualified for this. My own attitude about money could best be described as a writhing snakepit of neuroses. These issues have been with me since childhood; growing up, there never was quite enough to make ends meet, let alone overlap. My dad was suspicious of wealth and those who held it. It was the seventies, in Canada, and socialist ideals were still very much alive. I grew up believing it was a moral defect to have more than what you needed to get by.

"There is enough for everyone's need," said Gandhi, famously, "not for everyone's greed." As I received this ethic, the emphasis was all on "greed". The "enough" part didn't register. This makes for a nice cocktail of anxiety stirred up with guilt and self-reproach. Oh, and a twist of bitter.

Since moving to the United States, I have an abundance of opportunities to work on this particular corner of my belief system. I have been here ten years now, and how much people have is still staggering to me. Maybe I would have an easier time with this if it weren't offset by how very little others have--right here in this city, never mind across the globe. Until I came here I had never known so many people with trust funds and maids and fully appointed vacation homes. Until I came here, I had never met anyone who involuntarily lived without electricity or running water or health insurance.

I have a hard enough time making sense out of this for myself, let alone explaining it to a child. Once on the way home from school, my son wanted to know why he couldn’t buy his lunch at school everyday. I tried talking to him about how different people do different kinds of work for different kinds of pay. I explained that Daddy and Mommy could have become doctors or lawyers and made more money than we do as a graphic artist and writer, but that we probably would not be happy doing those things, and wasn’t it so much better than a hot lunch everyday to have a Mom and a Dad who were happy and fulfilled and had more time to spend with their children? Then I had to account for doctors and lawyers being worth so much more than artists and writers. Except his grandmother, who, granted, is a lawyer, but chose to defend poor people and not make a lot of money. Which brought us to the whole question of inherited wealth.

“Why didn’t we go to med school,?” I said to Patrick as I hung up my son’s backpack. “What were we thinking?”

I have a number of friends and acquaintances I consider economically privileged. I know that each and every one of them, like me, tries hard, means well, and hopes to get out of here without inflicting serious harm on anyone. Some of the wealthiest people I know are also the most generous; and from time to time, my children and I have been the grateful beneficiaries of this. Do I really believe that the extra resources they have means somebody somewhere else has less? I try not to.

Zero-sum thinking, in which there is a finite quantity to go around, is frowned upon here. A whole theology and industry has sprung up in recent years to make everybody feel spiritually okay about making money, and I try hard to get on board that train. I say mantras like “money is just energy” and “it’s what you do with it” and “the universe is abundant”, but I guess my lack of conviction weakens the signal I am putting out because I keep repelling wealth, not attracting it. When a little money does come my way, it is as if I have been contaminated with a corrosive substance, and I must be cleansed of it as quickly as possible. This is not a mentality I want to pass down to the next generation, anymore than I want them assimilated into the culture of consumerism.

As with everything else in this country, it is hard to find the middle way.

A few years back, a friend invited the children and I to be her guests for the Fourth of July celebrations at the country club. We had a wonderful time, and I sincerely hope they will let us come back again, publication of this essay notwithstanding. There was a magician and a juggler and a man on stilts dressed as Uncle Sam. There were elaborate inflatable tunnels and trampolines. There were white tents and buffet tables draped in linen and silver wine urns on the bar. Everyone was beautiful and smiling. No-one seemed sweaty or rumpled or cross. After the sun went down, there was a private fireworks display above the golf course that easily rivaled the public pyrotechnics downtown. I felt as if I had entered a secret and enchanted world.

My grandmother Mary would have said, I was "in the fairy." The day had that hypnotic, surreal quality; a midsummer night's dream. From the slope of the fairway, the river and the city below were framed in perfectly, like a classically proportioned painting. It was a point of view I had never seen before and one the majority of residents of this city will never see. It was stunning.

It occurred to me that for many of the people there, this was the world they lived in. This was how one usually spent the Fourth of July. I wondered what on earth would ever propel any of the people there to seek out an alternate perspective. I thought how hard it must be to bring up children in that world, where the answer to "can I have" could always be "yes, of course" and you have to come up with reasons why not, instead of the answer being a simple statement of fact. I left that evening with a new respect for my friend—and anyone else acclimated to that lifestyle—who manages to stay even remotely in touch with broader reality.

I was also aware that I too am privileged in my own way, because I can come and go from the fairy and they belong to it.

Last night, my son came to me and asked if we could order some collectible plush toys, his latest passion. You can just get them on the computer, my son told me, confidently and expectantly, his friend did. I looked at my beautiful child, freckled from his afternoon at the pool, and thought how I much I want to give him everything. I know that if money were no object, I would have been hard pressed to resist that impulse. I would have waved my magic wand and bought him the whole damn lot just to see his pleasure. Presto. As it was, I smiled and told him it would be a great thing to save for.

It would have been easy to feel sorry for him, and for myself, especially on the heels of the letter from the financial aid office and being between accounts receivable right now and down to pilfering quarters out of the loose change jar. Patrick's billing has gone out, and checks will start coming in, and the sky isn't about to fall, I know, but we are feeling just a little vulnerable.

I needed a distraction, and one that didn’t involve a credit card. So I brought the baby upstairs and sat with him in his brothers' room, playing with toys. Almost absent-mindedly, I started sorting through old puzzles laying strewn about. I started putting them together to see which had missing pieces and could be thrown out. Then I moved on to the toy basket, filling a laundry hamper with giveaways. One thing led to the other like that, until I could see all the extra stuff in the room that needed to be let go. I posted a notice on freecycle and we had our five dollar Friday night pizza and walked to grocery store for popsicles. When we got back, I checked email and read carefully through the dozen or more responses I already had to my offer of toys and clothes. I wrote back to a woman who sounded like she had the most urgent need, and told her to come and pick them up anytime over the weekend. I felt rich. I knew I had exactly what I needed for the day, and then some.

I looked at my boys, delighted with their 25 cent popsicles, the coveted toys forgotten about for another day. I thought about the kindergarten classmate who came to our backyard campout last year with his new video game still in its wrapper and who was horrified to learn we were going to eat hotdogs off sticks. I remembered attending a friend's booksigning a few month's ago, when an anecdote came up about another writer. "Well, you know she's never had to want for anything," somebody remarked. This was understood by all present as a handicap, a condition for which to make allowances. I thought about some of the people I've met whose lives have been messed up by too much or not enough money, and I felt suddenly, extraordinarily lucky. In a world of extremes, how easy it would have been for fate to overshoot and plant us at one end of the scale or the other, but we get to be right in the middle. To have just enough.

I wish I could occupy that place of gratitude always. I wish I wouldn't be insecure and grasping and envious, (although I will likely be again before the day is out) and I wish I could teach my kids how not to be those things either. I don't know if more money would insulate us from those feelings, but I am afraid of what else it would keep out, or trap in. I know as long as I remain frightened of wealth, I will probably never achieve it, but maybe I'm okay with that. Maybe it's better for us not to wander too deep in the fairy, to lose our way dreaming the American dream.

Labels: lack and plenty

this post lives all by itself here